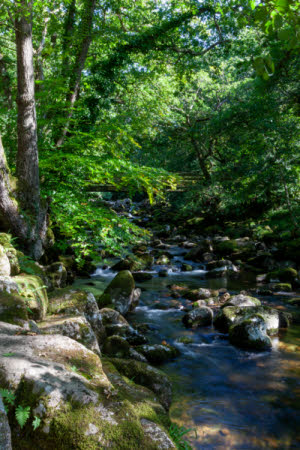

What wildlife rich looks like:

Clear, unpolluted water in a natural channel that reflects the local geology and conditions and is teeming with wildlife. The banks and surrounding land are diverse and create a natural wildlife corridor that weaves through the landscape.